An In-depth Guide to Surgical Staples: Types, Uses, & How to Use Them

An In-depth Guide to Surgical Staples

Surgical staples are commonly used in healthcare to close a wide variety of wounds during surgery. They are put in place using a surgical stapler. The staples may be made out of an alloy, and these types are not suitable for use in patients with metal allergies, e.g. nickel, but there are alternatives available, such as plastic. Staples are frequently used over sutures because they are faster and may give a more accurate, consistent result.

In this article, we detail the history of surgical staples and how the technology has evolved, contributing to the development of modern surgical techniques, as well as information about when surgical staples should be utilized and how to use them.

A Brief History of Surgical Staples

The development of surgical staples began in the nineteenth century thanks to surgeons Christian Albert Theodor Billroth and William S. Halsted.

Surgeon Theodor Billroth Operating (~1890)

Austrian surgeon Billroth was born in Prussia and became a pioneer in gastrointestinal surgery who developed the Billroth I and Billroth II procedures. The Billroth I is a ‘subtotal gastrectomy’ used to treat peptic ulcers and involved removing as much as 70% of the stomach before maintaining gastrointestinal continuity by performing a gastroduodenostomy to reattach the stomach and duodenum. The technique is still used today, albeit in a more refined form that only removes up to 50% of the stomach.

The Billroth II is a variation on the Billroth I procedure and is used in circumstances where a gastroduodenostomy would be difficult, e.g. due to a short abdominal esophagus, and reattaches the stomach to the jejunum.

The Billroth I and II procedures set a benchmark for gastrointestinal anastomoses. A surgical anastomoses, a procedure where a new, artificial connection is made between two separate fluid-carrying body structures, e.g. blood vessels or bowel. This was then further developed by New Yorker William S. Halsted, who was considered to be the father of modern American medical education. He established good practice guidelines for anastomosis and tissue management, calling for the use of small-gauge sutures and needles combined with skilled surgical methods and the minimization of tissue trauma. As part of his methodology, he discovered that single-layered anastomotic sutures gave results that were as good as double-layered sutures, but with less potential tissue damage.

In 1910, Halsted developed a prototype device that would enable non-suture anastomosis, but his invention did not make it to the market. However, his work laid the foundation for the creation of surgical staplers that applied a single layer of staples to close wounds during surgery.

Initially, other types of devices were trialed, some inspired by the sewing machines of the time. It was clear that there was a need for automated devices and clamps to assist surgeons in optimizing their suture placement. However, these early inventions did not prove popular and it wasn’t until 1908 that Hungarian Dr. Humer Hultl developed the first surgical stapler.

Dr. Hultl’s initial stapler contained some of the features that are still used in modern devices. Although it was hefty, weighing a whopping 8 pounds (3.6 kgs) and was difficult to manipulate needing two hours to set up and load, it was designed to minimize the chance of leakage through the staple line and featured ‘B’ shaped staples that were placed in four staggered rows of wire staples. Nowadays surgical staplers typically only place two or three staggered rows and use titanium staples.

Dr. Hultl sold just 50 of his surgical staplers. This was partly due to the expense and problems with reloading, but there was also the simple fact that many surgeons were reluctant to try out new technology. Nevertheless, Hultl’s stapler inspired another Hungarian, Dr. Aladár Petz, to improve on the design. The Von Petz stapler was much lighter and easier to manipulate and used silver staples. A major bonus was that it was much cheaper and Von Petz staplers were sold globally, making it easier for surgeons to see for themselves the benefits of this modern innovation.

There were problems with the Von Petz stapler. Surgeons could only use it once during surgery. It would need to be cleaned, reloaded and sterilized before a second use. This changed in 1934 when German Dr. H. Friedrich developed the replaceable cartridge which allowed the stapler to be used multiple times. This new stapler design allowed for adjustable tissue compression and paved the way for the development of a ‘triangular’ technique of end-to-end anastomosis that had not been previously possible.

In the mid-twentieth century, the Scientific Research Institute for Experimental Surgical Apparatus and Instruments was set up in Moscow due to the demand for quality training for surgeons who would be carrying out complex procedures far away from main cities. As well as providing training and education, the Institute was instrumental in developing surgical equipment, including a range of single line, linear cutter and circular staplers to be used in a range of circumstances. This was groundbreaking, but since all the devices were made by hand, individual parts were not always interchangeable.

In 1958, American Dr. Mark M. Ravitch was visiting the Moscow Thoracic Surgical Institute where he and three other American doctors were able to observe the use of the bronchial stapler and evaluate the patients it had been used on. It was sheer chance that led Dr. Ravitch to purchase one of these staplers in a store whereupon he was able to have it calibrated by staff at the Thoracic Institute so that he could take it back to America to use in his own surgery.

Working alongside Dr. Felicien Steichen, Dr. Ravitch started to experiment with his new device. Their combined efforts are largely responsible for the development and improvement of the linear stapler, the linear cutter, and the circular stapler, tools which are still in use today.

Their work was then built upon by the American medical industry, leading to the development of reloadable reusable surgical staplers and disposable reloadable surgical staplers. This also had a positive effect on surgical techniques. As laparoscopic surgery became common practice in gynecology, this led to the development of laparoscopic surgical staplers.

We continue to see innovation in this exciting field. New stapling technologies are being developed all the time. Recent developments have included tools that allow for the viscoelastic behavior of tissue when rapidly compressed, staplers that can provide multiple height staple lines, and microstaplers to name just a few. NOTES (Natural Orific Transluminal Endoscopic Surgery) has seen the invention of smaller surgical staplers that can be passed through a flexible endoscope allowing for greater control and choice.

We are still a long way from having exhausted all the possibilities offered by surgical staples and staplers.

The Different Types of Surgical Staplers

Surgical staplers are used in a wide range of surgeries, and are specialized for specific purposes, whether that be during the removal of part of an organ (resection), cutting through an organ or tissue (transection) or connecting structures together (anastomoses). A surgical stapler comprises of the stapler body, a staple cartridge/reload with lines of staplers, an anvil, and a firing mechanism. The surgeon loads a staple cartridge into the stapler (unless they are using a preloaded device) before placing the tissue to be connected between the stapler jaws (comprising of the cartridge and anvil). They then activate the firing mechanism to shoot a staple into place. Some types of staplers also include a knife that transects tissue as the stapler is fired.

Surgical staplers have enabled the development of more complex surgical techniques while at the same time reducing the amount of time required for surgery. They are available in a range of sizes and versions to allow for ease of use. Surgical staple removers are also available for removing the staples when appropriate.

Linear cutting staplers are used in the resection and transection of organs and/or tissues in abdominal, thoracic and pediatric surgery as well as gynecology. Designed for effective anastomosis, they have a knife built into the stapler body to allow for cutting as well as joining tissues and organs.

Linear staplers are designed for the anastomosing of organs and tissues.

Circular staplers are used in general surgery as well as thoracic surgery, bariatric surgery and colo-rectal surgery. They are designed to enable end-to-end, side-to-end and side-to-side anastomoses and, as the name suggests, place staples in a circular shape consisting of two concentric rings.

The Different Types of Surgical Staples

Internal leakage from badly executed suturing of the bowel is a major contributing factor to post-surgical mortality rates. Surgical staples have been a revolution in eliminating the risk of this. They may be left in the body, e.g. after clamping blood vessels, but are unlikely to cause any problems to the patient when this is necessary.

However, not all staples are suitable for all types of surgery and using the wrong type can have serious consequences. This is why different sizes and shapes have been developed to accommodate different tissue types and circumstances. This is a summary of the most commonly used types of staples.

Circular Staples

Circular staples, sometimes referred to as EEA devices, are usually used when attaching a vessel to the side of a larger vessel, a process known as end-to-end anastomosis. End-to-end anastomosis is carried out after bowel resection that has been performed to remove a diseased section of the large intestine and circular staples are the preferred method of closing the wounds. Circular staples are also used in cervical esophagogastric anastomosis following the elimination of cancer cells in the area. This approach is becoming more popular over suturing since circular staples can mean a shorter surgery time.

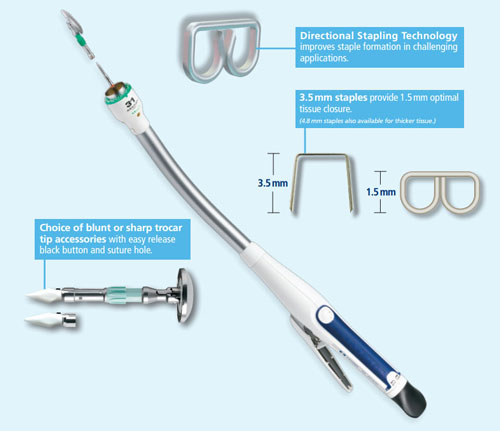

Laparoscopic Staples

Laparoscopic staples have been adapted for use in laparoscopic surgery. They are longer and thinner than the staples used in circular staples so that they can be easily manipulated through trocar ports and are used for end-to-side anastomosis. Laparoscopic surgery is less invasive than traditional surgical techniques and laparoscopic staples are left in the patient’s body tissue. They are used for a range of surgery types, including liver resection, removing a kidney affected by cancer and gastroplasty surgery.

Titanium Staples

Typically stainless steel is the material used in skin stapling and clips but titanium is generally preferred for internal surgeries due to its flexibility, strength and lightweight nature. The International Titanium Association claims that titanium is less likely to trigger a reaction from a patient’s immune system and easily adhere to bone and tissue. Titanium staples are not pure titanium. All surgical staples include a certain percentage of nickel. This means that it should be determined whether a patient has a nickel allergy and, if so, any possible side effects need to be discussed with their surgeon before proceeding with the surgery.

Surgical staples placed to close a wound by a veterinarian

Choosing the Most Appropriate Method to Close a Wound

Surgical staplers have a wider application than just for surgery. They can also be used externally to close wounds.

Approximately 7 million traumatic wound lacerations are treated in emergency rooms and countless more dealt with in practitioner’s offices. Ideally, in each of these situations, medical professionals should have access to a wound closure technique and/or device that:

- Is easy and fast to use

- Gives consistent results

- Is appropriate for all clinical scenarios

- Gives high quality cosmetic results

- Is affordable.

Although there are a number of options available – staples, sutures, surgical tapes and tissue adhesives – none of them fulfil all of these criteria, which means that in any given situation, a choice needs to be made for the best solution for a specific circumstance.

Most lacerations, particularly wounds that are half an inch in length or longer, will benefit from the use of some form of closure. Not only does this minimize the chance of infection, it will also improve the appearance of the healed skin, help stop bleeding and enable a faster return to normal function.

Stitches

When a patient has stitches, silk, nylon or polypropylene threads are used to sew through the skin to close a wound. Usually, the stitches will be left in for a few days until the wound is sufficiently healed for them to be removed, but sometimes, absorbable synthetic or animal-derived stitches are used, which will be broken down naturally by the body over time. Absorbable stitches are generally used as part of a multi-layer wound closure when it would be difficult to remove them, since they are in a deep tissue level.

Staples are most frequently used to close deep lacerations when it would be difficult or awkward to use sutures. As well as during surgery, they may also be used for wounds on the abdomen, leg, arm, scalp or back, but are not advised for use on the neck, feet or face.

Other alternatives for wound closure are surgical tapes and tissue adhesives. These are relatively modern innovations, and the Federal Drug Administration has only started supporting the general use of tissue adhesives over the last 20 years. (Although the first successful use of tissue adhesive was in 1959.) Clinical trials are therefore only available for the past couple of decades, with the first randomized controlled clinical trial examining the use of tissue adhesives in pediatric facial lacerations being carried out in 1993.

Tissue Adhesives

Tissue adhesives are best suited to low tension or linear lacerations, as well as for use underneath casts and splints or when dealing with fragile skin. The main features of tissue adhesives are:

- It is a method that is quick and easy to master

- There is no need to remove the adhesive

- There is no use of a needle

- It leaves a microbial barrier to protect the wound

- It is possibly less painful than other methods and gives a more comfortable result

- It has less tensile strength and carries an increased risk of dehiscence

- It is less resistant to moisture

- Some patients may suffer a skin reaction

Surgical Tape

Surgical tape is useful for low tension or linear lacerations, as well as for use underneath casts and splints and with fragile skin. It is also helpful to provide extra support for suture and staple removal. The main features of surgical tape are:

- It is a procedure that is quick and easy to master

- There is no need to use a needle

- It may be less painful than other methods and gives a more comfortable result

- It is economical

- Skin reactions are rare, although some patients report them

- It has less tensile strength and carries an increased risk of dehiscence

- It may require a specialized device to remove

- Tape may fall off before the wound is fully healed

- The wound must be kept dry since the tape is not resistant to moisture

Wound Closure: Stitches vs. Staples

With deep lacerations, whichever method is used, there will be some scarring, but stitches and staples give comparable cosmetic results and this should not be a factor in deciding which one to choose. In general, medical professionals choose based on their personal experience, skill level, and preference, but there are a few other features to bear in mind when comparing stitches to staples:

- Staplers are easy to learn how to use, although further training may be required as technology is updated

- Staples are usually easier to remove than stitches

- Staples allow rapid wound closure and are up to four times faster than suturing

- There is usually less inflammation with staples and there is a lower risk of infection/reaction

- Staples need a specialized tool for removal

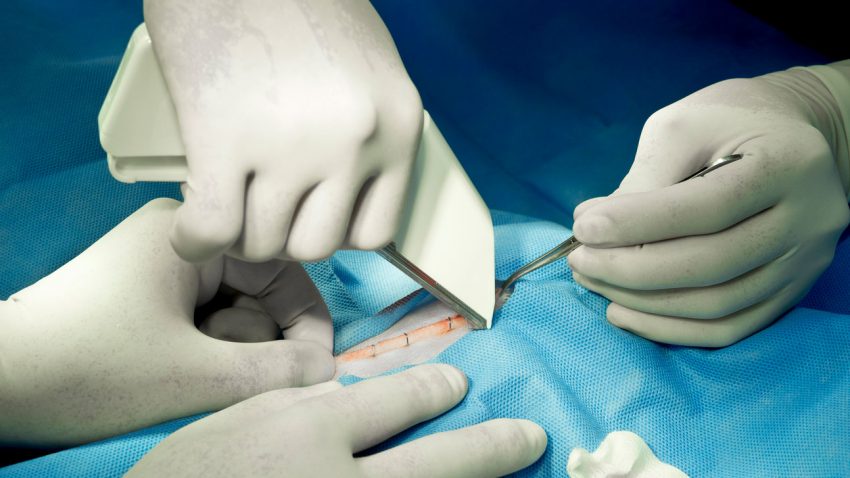

- Staples usually need two healthcare professionals to administer them: one to use forceps to align the two tissues to be joined while the other places the staples. It is crucial to have the tissues in the right place to enable optimum healing.

- Some patients may have psychological problems with the notion of stapling so may need extra support if staples are preferred over the alternatives

- Stitches have a long history of use and proven safety record

- Stitches can be removed with ordinary scissors

- Stitches only need one medical professional to close a wound

- Stitches are cheaper than staples

- There is a risk of needle stick and there may be a skin reaction to the sutures

When it comes to choosing staples over stitches and vice versa, attitudes are constantly shifting as research demonstrates which approach is better suited to any given situation. For example, surgeons have been inclined to use staples after a cesarean section because of how quick and easy they are to use, but recent research suggests that sutures have a 57% less chance of developing complications, with sutures 80% less likely to result in wound separation of 1cm or more. However, many surgeons still prefer to use staples following c-sections partly out of tradition but also because they are faster which makes them not only cost effective but also less likely to result in infection, which is associated with longer surgery time. Thus staples may be better suited to patients with a greater risk of complication, e.g. those who are obese, diabetic or have had repeat surgery.[1]

How to Remove Surgical Staples

Surgical staples require a specialized staple extractor to be removed. Before removing them, the wound should be inspected to confirm that it has healed sufficiently to allow for staple removal and checks should be made for any specific instructions surrounding removal. In general, staples are removed in two stages. At first, every other staple should be taken out with the rest following at a later date. Usually, all staples will be taken out within 7-14 days.

Although every facility will have their own specific protocol for staple removal, as a general guideline, there are a number of safety considerations that need to be taken into account. These include:

- Ensuring that hands are washed and all equipment is sterilized

- Ensuring the room is appropriate for staple removal

- Confirming that the correct patient is presenting for staple removal e.g. by checking two separate identifiers such as full name and date of birth

- Explaining to the patient what will happen during the procedure and offering various options to support the patient such as analgesia or use of bathroom

- Respecting the patient’s privacy and dignity at all times while paying attention to patient cues

Once all safety checks have been carried out, these are the steps involved in staple removal:

- Confirm that the lead physician has ordered that the staples be removed and explain the process to the patient so that they know what to expect. This will help minimize patient anxiety and make it easier for the patient to comply with the procedure. They should be aware that staple removal should not be painful but some tugging or pinching is normal.

- Make sure all the necessary equipment is to hand and sterilized where appropriate, including staple extractors, dressing tray, gloves, saline, surgical tape and outer dressing.

- Get the patient in a good position to allow for easy access for the medical professional while the patient is as comfortable as possible, respecting their privacy at all times.

- Carry out hand hygiene to minimize the chance of infection.

- Prepare all necessary equipment so that everything is readily available during the procedure.

- Remove the existing dressing and visually inspect the wound, checking that the edges are closed and ensuring there is no sign of leakage, redness and/or inflammation. If there are any concerns, consult the appropriate healthcare professional before proceeding.

- Put on gloves to minimize the chance of contamination.

- Clean the site of the incision to minimize the risk of infection as well as removing any dried blood or crusted exudate from the area.

- If this is the first time staples have been removed, remove every other staple, leaving the remainder for a later date. Place the lower tip of the staple extractor underneath the staple taking care not to pull upwards or changing the position of your wrist/hand while closing the handle. Once the handle is fully depressed, carefully wriggle the staple from side to side to take it out.

- Once you can see both sides of the staple, take the staple extractor away from the patient and over to a prepared area. Release the handle to place the staple on a sterile piece of gauze. If the patient reports feeling any pain during this process, take short breaks to allow the patient to deal with the sensation and encourage them to breathe deeply and relax as much as possible.

- Replace the removed staple with sterile surgical tape. Make sure the tape stretches to 1.5-2 cm either side of the incision.

- Repeat this process for every second staple along the line so that separation does not occur.

- Once all the staples have been removed, place a dry, sterile dressing on the wound. Alternatively, if the area will not be affected by clothing rubbing against it or if the physician has specifically ordered, leave the incision site exposed to air.

- Reposition the patient so that they are comfortable and pain free. Should there be any discomfort, supply the patient with analgesia as appropriate.

- Make sure the patient understands how to maintain their wound site. Advise them to take showers not baths and instruct them to leave the surgical tape in place until it falls off by itself. Also make sure the patient understands that they should not strain when toileting and that they should get plenty of rest, fluids and nutrition.

- Discard all disposables according to the facility’s protocols for dealing with sharps and biohazard waste. If a reusable staple extractor was used, send this for sterilization.

- Finally, carry out hand hygiene again and document all aspects of the procedure according to protocol. Should there be any unusual activity or concerns about the staple removal, make sure that these are promptly reported as appropriate.

Although staple removal is usually a straightforward procedure, complications do sometimes occur. Wound dehiscence (when the wound has not properly healed and separates) is still a concern, and healthcare professionals should be on the alert for this. Patients with an increased risk of dehiscence include: obese patients; patients over the age of 75 years; patients with COPD, cancer, anemia, sepsis, or diabetes; patients who are malnourished; patients who are anemic; patients who smoke; patients with a history of chemo- or radiotherapy. If there are any problems during the procedure, advice should be sought from a physician immediately.

Surgical Stapler Safety

On average, there are 8-9,000 adverse event reports per year concerning surgical staplers. The overwhelming majority of these were down to malfunctions (90%) with 9% concerning injuries. Less than 1% of the adverse events involving surgical staplers resulted in death.[2]

The most frequent types of malfunctions were that staples did not form, the stapler misfired or did not fire at all, and suture lines separated. The injuries experienced by patients were most commonly anastomosis failure, prolonged surgery, bleeding and infection.

The use of surgical staplers has superseded the need for manual suturing in many instances and in most cases this results in an easier surgery for the patient, allowing the surgeon to carry out complex surgeries that would not be possible without staples. However, where there has been an equipment malfunction, the impact on the patient can be devastating or even fatal, even if the mortality rate is low.

In addition, user error can also be a contributing factor. Although the devices are simple to use, there is still an element of skill required. The correct stapling cartridge must be selected for the correct tissue thickness and the tissue should be appropriately positioned within the stapler jaws. The following issues are the most frequently occurring user errors:

- Stapler jaws not properly positioned on the tissue requiring stapling

- Incorrect stapler cartridge size for tissue thickness selected

- Tissue not evenly distributed in stapler jaws

- Stapler clamps on another instrument

- Incorrect tension on tissue during stapler

- Incorrect use of firing mechanism, e.g. firing trigger not pulled all the way or pulled too hard[3]

All of these errors can have a serious impact on the patient. When stapler jaws are incorrectly positioned, this can result in leakage, blood loss and/or staple line opening, all of which can extend or negate the surgery. If a problem occurs during vascular stapling, the resulting blood loss can be fast and extensive, necessitating immediate corrective surgery.

If a staple that is too small has been used, this could tear away from the tissue, opening up the staple line. Conversely, using an overly large staple could mean there are gaps in the staple line, which could result in leakage, which is a major cause of complications.

If the stapler hasn’t been properly fired, the staples will be formed incorrectly and may pull out of the tissue, opening up the wound.

Maintaining Up-to-date User Knowledge

Given the potential consequences of user error, it is crucial that medical professionals are skilled in using surgical staplers. Although on analysis the benefits of surgical staplers and the resulting shorter surgery time outweigh the risks for most patients, care should be taken to ensure that there aren’t any avoidable problems, especially now the Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program[4] can result in lower Medicare payments for facilities that do not take reasonable precautions to improve patient safety and long term results.

In the first instances, users of surgical staplers should read and familiarize themselves with the instructions for use so that they can more readily detect when something is wrong. However, not all potential complication will be detailed in the instructions, so it is important that all staff are aware that failures are always a possibility so that they can quickly and effectively tackle problems when they arise. If the stapler’s mechanism fails, being able to stay calm instead of reacting in panic will help minimize damage to the tissues/organs.

As well as analyzing the instructions, medical professionals using surgical staplers should also have in place contingency plans in the event of a malfunction. Have spare surgical staplers to hand so that if a device is suspected to be faulty it can be replaced immediately. In addition, make sure that clamps are available so that if a staple line fails, the wound can be closed off to minimize trauma.

Since surgical staples are made in a range of sizes and heights, it is important that the correct one is chosen for the task at hand. Most linear staplers come with at least three different staple heights and it is crucial that the right one is selected to avoid the possibility of leakage, bleeding, or dehiscence. At this present time, staple size is usually chosen based on experience and anecdotal evidence, which means that there is always the chance of the wrong size being chosen.[5]

With so many variables at play, including the type of stapler and staple, tissue site, compression time, tissue thickness, tissue compressibility, etc. it is crucial that surgeons update their knowledge base to take account of these factors, especially since there is also the human variable that should be factored in as well, i.e. the surgeon’s experience and technique.

Studies have shown that the individual surgeon’s experience with surgical staplers has a direct impact on successful procedures. A review carried out by the Royal Victoria Hospital in Belfast, Ireland found that while surgical staplers would give uniformity when creating anastomoses, the regularity of the staples would not make up for a lack of surgical technique and warned that regardless of technological advances, any problems with surgical technique would still cause issues.[6]

This was not the only study to identify a problem with surgical skill. A review of colon and rectal resections Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston uncovered the fact that 19% of these surgeries had experienced a technical error due to the surgical stapler. Among the faults reported were misfires by the surgeon and incomplete anastomosis, all of which led to an increased risk of complications such as gastrointestinal bleeding, transfusions and unplanned proximal diversions.[7]

It is therefore imperative that a surgeon has the skill and experience to handle surgical staplers in order to give a patient the best possible chance of a positive outcome.

The Future of Surgical Stapling

The surgical stapling market is growing and is predicted to hit USD 6.8 billion by 2024. [8] This rise is thought to be due to the growth in bariatric procedures and further developments in endoscopic surgery. As more and more types of surgery lend themselves to an endoscopic approach, it is expected that surgical staplers will become increasingly popular and will see corresponding technological developments to keep pace with surgical techniques.

We are still seeing improvements to the design of surgical staplers, such as the recent introduction of the ECHELON FLEX Powered Surgical Stapler by Ethicon and this means that there remain more innovations yet to be discovered.

With improved devices come improved results and with the speed advantage offered by surgical staplers, it is little wonder that they are increasingly preferred over sutures. Disposable devices are particularly in demand due to the lowered risk of cross-contamination while disposable plastic staples mean that patients with nickel or metal allergies can also benefit from this approach.

As the technology behind surgical staplers becomes increasingly advanced, the risk of infection is minimized, although users need to be aware of all the different types available so that they can choose the most appropriate tool for the situation at hand. This may require ongoing training to ensure that healthcare professionals are fully abreast of current devices and their usage.

If you are a medical professional, do you prefer to use sutures or staples? Why? Have you had surgical staples following a surgery? What was your experience of them? We’d love to know your thoughts in the comments.

Sources:

[1] https://www.medpagetoday.com/obgyn/generalobgyn/46692

[2] https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/GeneralHospitalDevicesandSupplies/ucm110739.htm

[3] https://www.ecri.org/Pages/User-Errors-with-Surgical-Staplers-Result-in-Patient-Injuries.aspx

[4] https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/HAC/Hospital-Acquired-Conditions.html

[5] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4168870/

[6] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2184859

[7] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20193897

[8] http://www.grandviewresearch.com/press-release/global-surgical-stapling-market

Further reading:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4168870/

http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/847252_4